Pavle Levi introduction: Hitchcock's Vertigo has a larger than life status.

It walks off the movie screen into our lives. There are film studies and film fandom of

Vertigo. Jean-Pierre Dupuy is the spirit behind this symposium. He came up with

the idea that Stanford should have a 50th anniversary celebration of Hitchcock's Vertigo

symposium on campus a year ago. Cinephilia is when the film is watching us. Psycho, Rio Bravo,

La Dolce Vita are examples. Vertigo also belongs in this group. It's like a

game of tennis and we have to hit the ball back when it comes our way.

Professor Dupuy's talk today is "Time and Vertigo".

[Definition of cinephilia:

the state of being haunted or excessively preoccupied

with images, themes, dialogue & personalities in cinema;

Book:

Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory (2005) by Marijke de Valck and Malte Hagener].

The lecture below was reconstructed from my six pages of notes

taken during Professor Dupuy's presentation. All the web links and additional notes

in [brackets] are mine. The graphics were done in Adobe Photoshop and arranged

in HTML Tables to simulate the PowerPoint presentation of Professor Dupuy.

The book covers may be different than those shown in his talk.

Jean-Pierre Dupuy:

I consider Alfred Hitchcock more that just a film director. He is

a philosopher and metaphysician. I'm a member of an "insider club" of his Vertigo.

T. S. Eliot said "In my beginning is my end." [first line of Eliot's poem East Coker (1940)]

1941 was an annus mirailis [remarkable year]— the year of my birth. That year saw the publication in

Buenos Aires of Jorge Luis Borges's first collection of short stories

El jardín de senderos que se bifurcan

(The Garden of Forking Paths).

Adolfo Bioy Casares's novel

La Invención de Morel

(The Invention of Morel) also appeared in 1941

[It won the 1941 First Municipal Prize for Literature of the City of Buenos Aires.

The first edition cover artist was Norah Borges, sister of Casares' lifelong friend, Jorge Luis Borges].

.jpg) The story was the inspiration for Alan Resnais's

Last Year in Marienbad

and also an influence on the TV series

Lost. The narrator of the novel is a fugitive

wound up in a desert island [somewhere in Polynesia]. Then a miracle happened— people

dressed in costumes arrived at the island. The fugitive falls in love with a costumed lady

named Faustine. He approaches her to express his feelings but something keeps them apart.

He notices that Faustine is always talking to a bearded tennis player called Morel, but

their conversation remains the same. Morel resembles the Doctor Moreau character in

H.G. Wells' science fiction novel The

Island of Doctor Moreau (1896). Morel's invention is a machine that captures people's souls.

Through looping, it can play back a recording of their past actions thus reproducing reality.

The fugitive inserts himself into Morel's machine so his soul could merge with Faustine

and their love could be forever. This invention of Morel's machine is none other than

transhumanism that's being espoused today in technological circles. Far from mere holograms,

real people are engaged using all five senses. Morel's machine is like the recreation of

Madeleine in Hitchcock's Vertigo. When all the senses are synchronized, the soul

emerges. When Madeleine existed for the senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch,

Madeleine herself was actually there for Scottie. This morning's lecture, Richard Allen

analyzed Vertigo comparing it to Oscar Wilde's Picture of Dorian Gray where

the portrait changed while Dorian remained ever youthful. In Vertigo the portrait

of Carlotta Valdez in the Legion of Honors remained the same, but the character Madeleine

changed to Judy and back to Madeleine again.

The story was the inspiration for Alan Resnais's

Last Year in Marienbad

and also an influence on the TV series

Lost. The narrator of the novel is a fugitive

wound up in a desert island [somewhere in Polynesia]. Then a miracle happened— people

dressed in costumes arrived at the island. The fugitive falls in love with a costumed lady

named Faustine. He approaches her to express his feelings but something keeps them apart.

He notices that Faustine is always talking to a bearded tennis player called Morel, but

their conversation remains the same. Morel resembles the Doctor Moreau character in

H.G. Wells' science fiction novel The

Island of Doctor Moreau (1896). Morel's invention is a machine that captures people's souls.

Through looping, it can play back a recording of their past actions thus reproducing reality.

The fugitive inserts himself into Morel's machine so his soul could merge with Faustine

and their love could be forever. This invention of Morel's machine is none other than

transhumanism that's being espoused today in technological circles. Far from mere holograms,

real people are engaged using all five senses. Morel's machine is like the recreation of

Madeleine in Hitchcock's Vertigo. When all the senses are synchronized, the soul

emerges. When Madeleine existed for the senses of sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch,

Madeleine herself was actually there for Scottie. This morning's lecture, Richard Allen

analyzed Vertigo comparing it to Oscar Wilde's Picture of Dorian Gray where

the portrait changed while Dorian remained ever youthful. In Vertigo the portrait

of Carlotta Valdez in the Legion of Honors remained the same, but the character Madeleine

changed to Judy and back to Madeleine again.

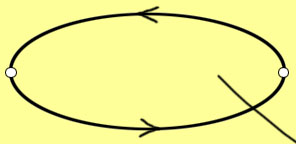

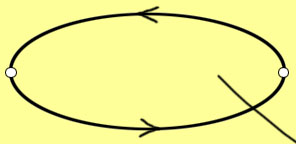

1) Linear Temporality— time is an arrow of decay with death at the end.

2) Circular Temporality— subjective reality in looping fashion;

no linear time; Faustine exists only in circular time that the fugitive

can't access to unless he inserted himself into Morel's machine.

In 1958, I was 17 years old when I saw Hitchcock's Vertigo in Paris. I fell in love

with Madeleine played by Kim Novak. In those days, you could stay in the theatre

and not pay for additional showings. I was glued to my seat and saw the film three times

in a row. Then I saw it ten times the first week, and 60-80 times since. As a 17-year

old teen, I began collecting celebrity magazines of Kim Novak. Little did I realize back

then that I made a categorical mistake. "Madeleine" was a pseudo woman who was false

and a fictional character within the fiction movie of Hitchcock. Madeleine's existence

was less than Gavin Elster than Scottie's love for her. Such an action can happen in life.

Love is dubious. Madeleine was possessed by Carlotta's spirit. She's fascinated by death.

.jpg) Denis de Rougemont wrote a

book L'Amour et l'Occident (Love in the Western World)) (1939, revised 1972)

that became a classic on romantic love.

[In this classic work, often described as "The History of the Rise, Decline, and

Fall of the Love Affair," Denis de Rougemont explores the psychology of love from

the legend of Tristan and Isolde to Hollywood. At the heart of his ever-relevant

inquiry is the inescapable conflict in the West between marriage and passion—

the first associated with social and religious responsiblity and the second with

anarchic, unappeasable love as celebrated by the troubadours of medieval Provence.

These early poets, according to de Rougemont, spoke the words of an Eros-centered

theology, and it was through this "heresy" that a European vocabulary of mysticism

flourished and that Western literature took on a new direction.]

(Google Book)

Denis de Rougemont wrote a

book L'Amour et l'Occident (Love in the Western World)) (1939, revised 1972)

that became a classic on romantic love.

[In this classic work, often described as "The History of the Rise, Decline, and

Fall of the Love Affair," Denis de Rougemont explores the psychology of love from

the legend of Tristan and Isolde to Hollywood. At the heart of his ever-relevant

inquiry is the inescapable conflict in the West between marriage and passion—

the first associated with social and religious responsiblity and the second with

anarchic, unappeasable love as celebrated by the troubadours of medieval Provence.

These early poets, according to de Rougemont, spoke the words of an Eros-centered

theology, and it was through this "heresy" that a European vocabulary of mysticism

flourished and that Western literature took on a new direction.]

(Google Book)

Tristan und Isolde is an opera (1859) in three acts by Richard Wagner

based on the romance by

Gottfried von Strassburg [d. 1210].

Just as Tristan though deeply in love with Isolde couldn't marry her because she's

bethrothed to King Marke, so Scottie can't marry Madeleine.

"The victory of passion over desire" and "The triumph of death over life"

are the themes in Vertigo. Scottie duplicated Madeleine as Elster did.

He sent Madeleine twice to her death. The moment Scottie understood what

Elster really did, he screamed at Judy/Madeleine on the Bell Tower at

San Juan Bautista: "You played his wife so well Judy! He made you over

didn't he? Just as I've done. But better! Who was at the top when

you got there? Elster!"

.jpg) The Sense of the Past

is an unfinished novel by Henry James, posthumously published in 1917.

[The novel is at once an eerie account of time travel and a bittersweet comedy of manners.

A young American trades places with a remote ancestor in early 19th century England, and

encounters many complications in his new surroundings.] Henry James wanted to rewrite

H.G. Wells' novella The Time Machine (1895).

Here's what Borges had to say on Henry James's The Sense of the Past in his

"La flor de Coleridge" (1937): "In The Sense of the Past, the link between the real

and the imaginary, that is to say between the present and the past, is not a flower, it is

a portrait, dating from the 18th century that mysteriously represents the protagonist.

Fascinated by this canvas, he succeeds in going back to the day when it was painted.

[Among the persons he meets, he finds, the artist, who paints him with fear and aversion,

having sensed something unusual and anomalous in those future features. James thus creates

an incomparable ‘regressus in infinitum’ when his hero Ralph Pendrel returns to the

18th century because he is fascinated by an old portrait, but Pendrel needs to have

returned to the 18th century for that portrait to exist. The cause follows the effect,

or the reason for the journey is a consequence of the journey]."

The Sense of the Past

is an unfinished novel by Henry James, posthumously published in 1917.

[The novel is at once an eerie account of time travel and a bittersweet comedy of manners.

A young American trades places with a remote ancestor in early 19th century England, and

encounters many complications in his new surroundings.] Henry James wanted to rewrite

H.G. Wells' novella The Time Machine (1895).

Here's what Borges had to say on Henry James's The Sense of the Past in his

"La flor de Coleridge" (1937): "In The Sense of the Past, the link between the real

and the imaginary, that is to say between the present and the past, is not a flower, it is

a portrait, dating from the 18th century that mysteriously represents the protagonist.

Fascinated by this canvas, he succeeds in going back to the day when it was painted.

[Among the persons he meets, he finds, the artist, who paints him with fear and aversion,

having sensed something unusual and anomalous in those future features. James thus creates

an incomparable ‘regressus in infinitum’ when his hero Ralph Pendrel returns to the

18th century because he is fascinated by an old portrait, but Pendrel needs to have

returned to the 18th century for that portrait to exist. The cause follows the effect,

or the reason for the journey is a consequence of the journey]."

A Literary Genealogical Tree for Hitchcock's Vertigo

H.G. Wells

The Time Machine (1895)

.jpg)

Henry James

The Sense of the Past (1917)

| H.G. Wells

Island of Dr. Moreau (1896)

.jpg)

Adolfo Bioy Casares

The Invention of Morel (1941)

|

.jpg)

Pierre Boileau & Thomas Narcejac

Among the Dead (1954)

D'entre les morts

|

.jpg)

Alfred Hitchcock

Vertigo (1958)

|

Chris Marker's

La Jetée (1964)

is a 28-minute black and white science fiction film. Constructed almost entirely from

still photos, it tells the story of a post-nuclear war experiment in time travel.

He understood there was [?]

.jpg) Bernard Herrmann's music contributed to 50% of the success of Hitchcock's Vertigo

Herrmann's score is heavily reminiscent of Richard Wagner's "Liebestod" in Tristan und Isolde,

most evident concerning the resurrection scene. In the scene where Madeleine first appears

at Ernie's restaurant, Herrmann's score is similar to the Prelude of Tristan und Isolde

when her profile is seen on the screen.

[Wagner's "Liebestod" midi file; Bernard Herrmann's film score;

Alex Ross, "Vertigo" (music), New York Times, Oct. 6, 1996]

Bernard Herrmann's music contributed to 50% of the success of Hitchcock's Vertigo

Herrmann's score is heavily reminiscent of Richard Wagner's "Liebestod" in Tristan und Isolde,

most evident concerning the resurrection scene. In the scene where Madeleine first appears

at Ernie's restaurant, Herrmann's score is similar to the Prelude of Tristan und Isolde

when her profile is seen on the screen.

[Wagner's "Liebestod" midi file; Bernard Herrmann's film score;

Alex Ross, "Vertigo" (music), New York Times, Oct. 6, 1996]

In "Kafka and His Precursors" [1951], Borges outlined Kafka's idiosyncracy:

We could create our own precursors:

Experience of projected time loop has to close upon itself:

|

Madeleine → Carlotta

Meaning |

|

Scottie &

Madeleine |

| Scottie &

Judy becoming

Madeleine again |

|

Causation | Necklace |

Scottie was in love with Madeleine who never existed!

[Gavin Elster's wife Madeleine Valdez never appears in the film except when her

corpse was dumped from the San Juan Bautista Tower by Elster. The "Madeleine" that

Scottie (Jimmy Stewart) fell in love with was an imposter Judy Barton whom Gavin

Elster hired to play his wife Madeleine (who was away in the countryside) as part

of the murder plot. When Scottie discovers this nefarious plot, he was furious

and dragged Judy/Madeleine up to the church tower, re-enacting the scene of the crime

with tragic consequences. "Madeleine", the ideal woman of his desire and love, was a projection

of Scottie— in reality just an illusion in his mind.

Scottie was to witness Madeleine's death twice falling from the Tower. (It's interesting

that Tarot Card #16 "The Tower" shows two people falling to their death.)

In one of his poems, Giacomo Leopardi wrote “Love, the last illusion of life.”

This is what Scottie experienced in his endless pursuit of Madeleine—

the love of his life. Scottie's despair was foreseen in

Leopardi's poem "To Himself".]

The perfect form is a circle.

[Note: Emerson's Essays: First Series, "Circles" (1841):

“The eye is the first circle; the horizon which it forms is the second;

and throughout nature this primary figure is repeated without end.

It is the highest emblem in the cipher of the world.”]

But in Hitchcock's Vertigo, the form is a downward spiral as seen

in the Title sequence by

Saul Bass [the camera zooms in on the

circle of the eye to a series of downward spirals along with Bernard Herrmann's

strident music accompaniment]. We also have Lissajous Curves revisited by

John Whitney and

Saul Bass during the

Title sequence.

In mathematics, a Lissajous curve is the graph of the system of parametric equations

x = Asin(at + δ), y = Bsin(bt),

which describes complex harmonic motion. This family of curves was investigated

by Nathaniel Bowditch in 1815, and in more detail by Jules Antoine Lissajous in 1857.

Wikipedia shows these

Lissajous curves with δ= π/2, a odd, b even,

|a-b| = 1:

No matter how curvaceous the path of these Lissajous curves, one always comes

back to the beginning. Hence the T.S. Eliot quote "In my beginning is my end"

and the fate of Scottie and Madeleine in Hitchcock's Vertigo. Merci!

***************************************************************

Addendum: I dropped by Jean-Pierre's office at 111 Pigott Hall around 3:30 pm on Monday, October 20.

I pointed out to him that after his Friday talk (10/17) on "Time and Vertigo", they removed the clock from

the Clock Tower on Sunday (10/19) for repair. The Clock Tower

visible outside his window is now timeless! I took a photo and wrote this haiku: "Clock Tower faceless /

without its "teller of time"— Now it is timeless!" Although he was leaving for Paris the next day

and busy doing last minute errands, we chatted a few moments,

and he thanked me for the Kim Novak and Alan Watts web pages I did for him. When I asked whether

he can send me his "Time and Vertigo" paper, he said it's still in draft form,

but will send it to me once he settles down in Paris. So this version will be revised once

I get his complete PowerPoint presentation. Meanwhile I've composed this early draft for friends

who were interested in Professor Dupuy's talk but couldn't attend the 50th Anniversary of Hitchcock's Vertigo

Symposium that was truly a learning experience.

|

(10-22-2008)

(10-22-2008).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg) The story was the inspiration for Alan Resnais's

The story was the inspiration for Alan Resnais's

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)