|

News On This Day |

| Saturday, June 14, 2003 | for my niece Elisa's wedding | by Peter Y. Chou |

|

Full Moon, Saturday, June 14, 2003, Thomas Fogarty Winery, Woodside, California— Wedding of Elisa Cheng & Ben Lubin  Elisa Cheng, daughter of David & Margaret Cheng, marries Benjamin Lubin, son of Steven & Wendy Lubin,

at the Thomas Fogarty Winery, Woodside, California. Bride & Groom met each other while studying at

Harvard University. A hundred guests were present on a bright sunny day overlooking the bay to celebrate

this joyful occasion filled with beauty and poetry. The finely engraved wedding invitation quotes Shakespeare's

Sonnet 76:

“For as the sun is daily new and old, / So is my love still telling what is told.”

The poetry continues on the wedding program with Robert Browning's “Grow old along with me! /

The best is yet to be” (

Rabbi Ben Ezra from Dramatis Personae, 1864). Poetry and song continued in the wedding

ceremony when Pablo Neruda's Love Sonnet IX

and Rilke verses were read, and Puccini's

"O mio babbino caro" was sung. The wedding processionals included Schubert's Impromptu in G Flat

and Wedding March by Steven Lubin, the bridegroom's father (composed for his wedding, June 2, 1974).

Pastor Joseph Steinke officiated the wedding and spoke inspiring words to the audience, telling them to look

at their loved ones and ask "Do I love him or her with the same intensity I did when we were first married?"

He tells the gathering that Elisa and Ben love each other so much that they selected this beautiful place

to share the joy of love with their family and friends. We are blessed to witness this marriage of bliss.

Elisa honored her grandparents who have passed on, saying “They showed us some of the best qualities

of life and love, and for that, we will always be grateful.” Elisa loved fairy tales as a child and

wrote prize-winning fairy tale stories in school. The cold fog up at Skyline that lasted for two days cleared up

in time for this happiest of happy days for her and Ben. Truly, Elisa has composed a lovely fairy-tale wedding,

sharing the beauty of her love with Ben and all her family and friends. May the warm sun, the gentle full moon,

and the sparkling stars bless this happy couple always.

(Elisa's Wedding Photos;

NY Times 6-15-2003, Weddings & Celebrations)

Elisa Cheng, daughter of David & Margaret Cheng, marries Benjamin Lubin, son of Steven & Wendy Lubin,

at the Thomas Fogarty Winery, Woodside, California. Bride & Groom met each other while studying at

Harvard University. A hundred guests were present on a bright sunny day overlooking the bay to celebrate

this joyful occasion filled with beauty and poetry. The finely engraved wedding invitation quotes Shakespeare's

Sonnet 76:

“For as the sun is daily new and old, / So is my love still telling what is told.”

The poetry continues on the wedding program with Robert Browning's “Grow old along with me! /

The best is yet to be” (

Rabbi Ben Ezra from Dramatis Personae, 1864). Poetry and song continued in the wedding

ceremony when Pablo Neruda's Love Sonnet IX

and Rilke verses were read, and Puccini's

"O mio babbino caro" was sung. The wedding processionals included Schubert's Impromptu in G Flat

and Wedding March by Steven Lubin, the bridegroom's father (composed for his wedding, June 2, 1974).

Pastor Joseph Steinke officiated the wedding and spoke inspiring words to the audience, telling them to look

at their loved ones and ask "Do I love him or her with the same intensity I did when we were first married?"

He tells the gathering that Elisa and Ben love each other so much that they selected this beautiful place

to share the joy of love with their family and friends. We are blessed to witness this marriage of bliss.

Elisa honored her grandparents who have passed on, saying “They showed us some of the best qualities

of life and love, and for that, we will always be grateful.” Elisa loved fairy tales as a child and

wrote prize-winning fairy tale stories in school. The cold fog up at Skyline that lasted for two days cleared up

in time for this happiest of happy days for her and Ben. Truly, Elisa has composed a lovely fairy-tale wedding,

sharing the beauty of her love with Ben and all her family and friends. May the warm sun, the gentle full moon,

and the sparkling stars bless this happy couple always.

(Elisa's Wedding Photos;

NY Times 6-15-2003, Weddings & Celebrations)

Philadelphia, June 14, 1777—

Continental Congress Adopts the Stars & Stripes as the First Flag of the United States

Sonoma: June 14, 1846— Republic of California Proclaimed

June 14, 1940— German Troops Occupies Paris in World War II

June 14, 1942— Walt Disney's Film Bambi Premieres

Bambi (1942),

Disney's Bambi,

Bambi Coloring Page,

Bambi Video Clip 1,

Bambi Video Clip 2,

Bambi Video Reviews at Amazon.com,

Bambi Disney E-cars,

Bambi Disney Video Lithographs,

Felix Salten: Deer Bambi,

Felix Salten (1869-1945): Bambi's Author,

Bambi, the Austrian Deer

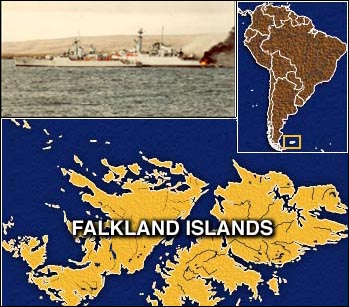

Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, June 14, 1982—

New York City: June 14, 1986—

Geneva, Switzerland: June 14, 1986—

Just a few words, dear friends, to tell you that I am very well and more and more finding out who I am,

learning to distinguish between what is really me and what is not. I am working hard and absorbing all

I can which comes to me on all sides from without, so that I may develop all the better fro within.

During the last few days I have been in Tivoli. The whole complex of its landscape with its details,

its views, its waterfalls, is one of those experiences which permanently enrich one's life...

One more observation. For the first time I can say that I am beginning to love trees and rocks,

and yes, Rome itself; till now I have always found them a little forbidding. Small objects, on the other

hand, have always delighted me, because they reminded me of the things I saw as a child. But now I am

beginning to feel at home here, though I shall never feel as intimate with these things as I did with the

first objects in my life. This thought has led me to reflect on the subject of art and imitation.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832),

Italian Journey, Rome, June 16, 1787

We had not been long at table before Herr Seidel was announced, accompanied by the Tyrolese. The singers

remained in the garden room, so that we could see them perfectly through the open doors, and their song

was heard to advantage from that distance... Fräulein Ulrica and I [Eckermann] were particularly

pleased with the "Strauss" and "Du, du liegst mir im Herzen", and asked for a copy of them.

Goethe seemed by no means so much delighted as we. "One must ask children and birds," said he,

"how cherries and strawberries taste." Between the songs, the Tyrolese played various national dances,

on a sort of horizontal guitar, accompanied by a clear-toned German flute... [News arrived that the

Grand Duke of Weimar died on his journey hither from Berlin. Since Goethe had worked intimately with

the Duke for over 50 years, this news was kept from Goethe. Later his son communicated the sad tidings

to his father.] I saw Goethe late in the evening. Before I entered his chamber, I heard him sighing and

talking aloud to himself: he seemed to feel that an irreparable rent had been torn in his existence.

All consolation he refused, and would hear nothing of the sort. "I thought," said he, "that I should

depart before him; but God disposes as he thinks best; and all that we poor mortals have to do, is to

endure and keep ourselves upright as well and as long as we can."

The Dowager Grand Duchess received the melancholy news at her summer residence of Wilhelmsthal...

Goethe went soon to Dornburg, to withdraw himself from daily saddening impressions, and to restore

himself by fresh activity in a new scene. By important literary incitements on the part of the French,

he had been once more impelled to his theory of plants; and this rural abode, where, at every step into

the pure air, he was surrounded by the most luxurious vegetation, in the shape of twining vines and

sprouting flowers, was very favorable to such studies... And, indeed, there was, from windows at such

a height, an enchanting prospect. Beneath was the variegate valley, with the Saale meandering through

the meadows. On the opposite side, toward the east, were woody hills, over which the eye could wander

afar, so that one felt that this situation was, in the daytime, favorable to the observation of passing

showers losing themselves in the distance, and at night to the contemplation of the eastern stars and

the rising sun.

"I enjoy here," said Goethe, "both good days and good nights. Often before dawn I am already awake,

and lie down by the open window, to enjoy the splendor of the three planets, which are at present

to be seen together, and to refresh myself with the increasing brilliancy of the morning-red. I then

pass almost the whole day in the open air, and hold spiritual communion with the tendrils of the vine,

which say good things to me, and of which I could tell you wonders. I also write poems again, which are

not bad, and, if it were permitted me, I should always to remain in this situation.

— Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832),

"Pray without ceasing"— It is the duty of men to judge men only by their actions.

Our faculties furnish us with no means of arriving at the motive; the character, the secret

self. We call the tree good from its fruits & the man from his works.

[This is the title and opening of Emerson's first sermon as pastor in Cambridge, Mass.]

— Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882),

Journal, Sunday, June 11, 1826

After a fortnight's wandering to the Green Mountains & Lake Champlain yet finding you

dear Ellen nowhere & yet everywhere I come again to my own place, & would willingly

transfer some of the pictures that the eyes saw, in living language to my page; yea

translate the fair & magnificent symbols into their own sentiments. But this were to

antedate knowledge. It grows into us, say rather, we grow wise & not take wisdom;

and only in God's own order & by my concurrent effort can I get the abstract sense of

which mountains, sunshine, thunder, night, birds, & flowers are the sublime alphabet.

Truth produces confidence in itself. Truth contains its ultimate reason. As a ball whose

heat increases lights its own path. Few are free. Truth makes free. The man who thinks

all good to consist in wealth, that is, the miser, not only mistakes, but is under

the dominion, as we say, of an error... You desist at once from a thousand enforced

works & words— you are free from this delusion. You are free to follow the natural

constitution of your mind & the Universe.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882),

Journals, June 15, 1831

On we came passing the fine Cascade of Pissevache & stopped an hour at St Maurice. Thence in

more convenient vehicles thro' a country of grandest scenery passing thro' Clarens & along the

banks of Lake Leman, by the Castle of Chillon then through Vevey & we reached Lausanne before

nightfall. The repose & refreshment of a good hotel were very welcome to us after riding two

nights; but the next morning (14th June) was fine, and Mr Wall & I walked out to the public

promenade, a high & ornamented grove which overlooks the Lake & commands the view of a great

amphitheatre of mountains. We are getting towards France. In the café where we breakfasted

we found a printed circular inviting those whom it concerned to a rifle-match, to the intent,

as the paper stated, "of increasing their skill in that valuable accomplishment, & of drawing

more closely the bonds that regard with which we are, &c," After breakfast I inquired my way

to Gibbon's house & was easily admitted to the garden. The summerhouse is removed but the floor

of it is still there, where the History was written & finished. I stood upon it & looked forth

upon the noble landscape of which he speaks so proudly. I plucked a leaf of the limetree he

planted, & of the acacia— successors of those under which he walked. I have seen however

many landscapes as pleasant & more striking. At 10 o'clock we took the steamboat for Geneva

& sailed up lake Leman. The passage was very long— seven hours— for the wind was

ahead, & the engine not very powerful. We touched at Coppet. The lake is most beautiful near

Geneva. It was not clear enough to see Mont Blanc or else it was not visible. Mount Varens

& Monte Rosa were seen.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 13-14, 1833

Power is one great lesson which Nature teaches Man. The secret that he can not only reduce under his will,

that is, conform to his character, particular events but classes of events & so harmonize all the outward

occurrences with the states of mind, that must he learn. Worship, must he learn.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 14-15, 1836

It is the distinction of genius that it is always inconceivable— once & ever a surprise. Shakspeare

we cannot account for, no history, no "life & times" solves the insoluble problem. I cannot slope things

to him so as to make him less steep & precipitous; so as to make him one of many, so as to know how I should

write the same things. Goethe, I can see, wrote things which I might & should also write, were I a little more

favored, a little cleverer man. He does not astonish. But Shakspear, as Coleridge says, is as unlike his

contemporaries as he is unlike us. His style is his own. And so is Genius ever total & not mechanically

composabel. It stands there a beautiful unapproachable whole like a pinetree or a strawberry— alive,

perfect, yet inimitable; nor can we find where to lay the first stone, which given, we could build the arch.

Phidias or the great Greeks who made the Elgin marbles & the Apollo & Laocoon belongs to the same exalted

category with Shakspear & Homer. And I imagine that we see somewhat of the same possibility boundless in

countrymen & in plain motherwit & unconscious virtue as it flashes out here & there in the corners.

When I read the North American Review, or the London Quarterly, I seem to hear the snore of the muses,

not their waking voice. I was in a house where tea comes like a loaded wagon very late at night. Read

& think. Study now, & now garden. Go alone, then go abroad. Speculate awhile, then work in the world.

Yours affectionately.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 13-15, 1838

It is a superstition to insist on vegetable or animal or any special diet. All is made up at last of

the same chemical atoms. The Indian rule shames the Graham rule— A man can eat anything: cats, dogs,

snakes, frogs, fishes, roots, & moss. All the religion, all the reason in the new diet is that animal

food costs too much. We must spend too much time & thought in procuring so varied & stimulating diet &

then we become dependent on it.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 14, 1840

We are too civil to books. For a few golden sentences we will turn over & actually read a volume of 4 or 500

pages. Even the great books. 'Come', say theym 'we will give you the key to the world'— Each poet each

philosopher says this, & we expect to go like a thunderbolt to the centre, but the thunder is a superficial

phenomenon, makes a skin-deep cut, and so does the Sage— whether Confucius, Menu, Zoroaster, Socrates;

striking at right angles to the globe his force is instantly diffused laterally & enters not. The wedge turns

out to be a rocket. I have found this to be the case with every book I have read & yet I take up a new writer

with a sort of pulse beat of expectation.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 1841

A highly endowed man with good intellect & good conscience is a Man-woman & does not so much need the complement

of Woman to his being, as another. Hence his relations to the sex are somewhat dislocated & unsatisfactory. He asks in

Woman, sometimes the Woman, sometimes the Man.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 14, 1842

Be an opener of doors for such as come after thee,

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journal, June 15, 1844

Every thing teaches transition, transference, metamorphosis: therein is human power, in transference,

not in creation; & therein is human destiny, not in longevity but in removal. We dive & reappear in

new places.

How attractive is land, orchard, hillside, garden, in this fine June! Man feels the blood of thousands

in his body and his heart pumps the sap of all this forest of vegetation through his arteries. Here is

work for him & a most willing workman.

Literature should be the counterpart of nature & equally rich. I find her not in our books. I know

nature, & figure her to myself as exuberant, tranquil, magnificent in her fertility— coherent,

so that every thing is an omen of every other. She is not proud of the sea or of the stars, of space

or time; for all her kinds share the attributes of the selectest extremes. But in literature her

geniality is gone— her teats are cut off, as the Amazons of old.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals, June 1847

I do not count the hours I spend in the woods, though I forget my affairs there & my books.

And, when there, I wander hither & thither; any bird, any plant, any spring, detains me.

I do not hurry homewards for I think all affairs may be postponed to this walking. And it

is for this idleness that all my businesses exist.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, Journals, June 1857

How often, when we have been nearest each other bodily, have we really been farthest off! Our tongues

were the witty foils with which we fenced each other off. Not that we have not met heartily and with profit

as members of one family, but it was a small one surely, and not that other human family... Thus much,

at least, our kindred temperament of mind and body— and long family-arity— have done

for us, that we already find ourselves standing on a solid and natural footing with respect to one another,

and shall not have to waste time in the so often unavailing endeavor to arrive fairly at this simple ground.

Let us leave trifles, then, to accident; and politics, and finance, and such gossip, to the moments when

diet and exercise are cared for, and speak to each other deliberately as out of one infinity into another—

you there in time and space, and I here. For beside this relation, all books and doctrines are no better

than gossip or the turning of a spit. Equally to you and Sophia, from

— Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862),

The seringo sings now at noon on a post; has a light streak over eye. How rapidly new flowers

unfold! as if Nature would get through her work too soon. One has as much as he can do to observe how

flowers successively unfold. It is a flowery revolution, to which but few attend. Hardly too much

attention can be bestowed on flowers We follow, we march after, the highest color; that is our flag,

our standard, our "color". Flowers were made to be seen, not overlooked. Their bright colors imply eyes,

spectators. There have been many flower men who have rambled the world over to see them. The flowers

robbed from an Egyptian traveller were at length carefully boxed up and forwarded to Linnaeus, the man

of flowers. The common, early cultivated red roses are certainly very handsome, so rich a color and so

full of blossoms; you see why even blunderers have introduced them into their gardens.

— Henry David Thoreau,

Journal, June 15, 1852

On leaving the house about eight o'clock at night, met the tall, pretty working girl. I followed her

as far as the Rue de Grenelle, always meditating what course to pursue and almost miserable because

I had the chance. I am always like that. I found afterwards, all sorts of ways to use in accosting her,

and when it was the right time for them, I opposed them with the most absurd difficulties. My resolutions

always evaporate when there is need of action... I have not enough simple, commonplace energy to overcome

the thing by busying myself some other way. As long as inspiration is lacking, I am bored. There are some

people who, in order to avoid boredom, know how to set themselves a task and accomplish it.

— Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863),

Journal, Monday, June 14, 1824

An architect who really fulfills all the conditions of his art seems to me a phoenix far more rare

than a great painter, a great poet, or a great musician. It is absolutely evident to me that the reason

for this resides in that absolutely necessary accord between great good sense and great inspiration.

The details of utility which form the point of departure for the architect, details which are of the

essence of things, take precedence over all the ornaments: and yet he is not an artist unless he lends

fitting ornaments to the usefulness which is his theme. I say fitting; for, even after

having established the exact relationship of his plan withevery aspect of customary usage, he cannot

embellish this plan save in a certain manner: he is not free to be lavish or sparing with ornaments;

they are compelled to be as appropriate to the plan as the latter has been to customary usage. The

sacrifices which the painter and the poet make to grace, to charm, and to the effect on the imagination,

excuse certian things which exact reason would condemn as false. The only license which the architect

permits himself may perhaps be compared with that which the great writer indulges in when, to a certain

extent, he creates his own language. When he uses terms which are of the current speech of everybody,

the special turn he gives them makes of them new terms; in the same way, by the employment, at once

calculated and inspired, of ornaments which are within the domain of all in his possession, the

architect gives to them a surprising novelty and reaches that form of the beautiful which it is given

to his art to attain. An architect of genius will copy a monument and will be able, by variants, to

render it original; he will render it fitting for its place, he will observe in distances and proportions

such order that he will make it completely new. The common run of architects can copy only in a literal

way, and so, to the humiliating confession of their impotence which they seem to make, they add lack of

success even in imitating; for the monument they build, an imitation to the last detail, can never be in

exactly the same conditions as the one which they imitate. Not only are they unable to invent a beautiful

thing, but they spoil the fine original creation which, in their hands, becomes a flat and insignificant

thing, as we are so surprised to discover. Those whose procedure is not to imitate en bloc and with

exactitude, work haphazardly, so to speak; the rules teach them that they have to ornament certain parts,

and they ornament those parts, whatever the character of the monument and whatever its surroundings.

— Eugene Delacroix,

Journal, Friday, June 14, 1850

The execution of the dead bodies in the picture of Python [ceiling of the Galerie d'Apollon],

that is my real execution, the one suited to my temperament. I should not paint that way from nature,

and the freedom that I get in this way compensates for the absence of the model. I must remember the

characteristic difference between this and the other parts of my picture.

— Eugene Delacroix,

Journal, Saturday, June 14, 1851

After dinner, took a walk in the park with young Rodrigues, a babe at the breast of painting,

getting his milk from Picot

[François-Edouard Picot (1786-1868)], and tiring me a little with his naive conversation;

but thanks to his good will, I got some fresh air amidst the most beautiful trees in the world.

— Eugene Delacroix,

Journal, Champrosay, June 14, 1855

I sit next to Aubert at dinner,

at the Hôtel de Ville. He tells me that despite a happy life,

he would not want to begin again to live, because of those thousand bitternesses with which life is

sowed. This is the more remarkable because Aubert is a complete voluptuary: at his present age, he can

still take enjoyment in the company of a woman. The sovereign good would therefore be tranquillity.

Why not begin early with giving to tranquillity its pre-eminent position? If man is destined one day

to find out that calm stands above all else, why not give oneself a life which can afford that

anticipated calm, while still containing some of those sweet enjoyments which are not the same thing

as the fearful upheavals caused by the passions? But how one must watch oneself if one would be spared

them, when they are so greatly to be feared!

— Eugene Delacroix,

Journal, Thursday, June 14, 1856

From what you say Dear Austin I am forced to conclude that you never received my letter which

was mailed for Boston Monday, but two days after you left— I don't know where it

went to... Your room looks lonely enough— I do not love to go in there— whenever I pass

thro' I find I 'gin to whistle, as we read that little boys are wont to do in the graveyard. I am

going to set out Crickets as soon as I find time that they by their shrill singing shall help

disperse the gloom— will they grow if I transplant them? You importune me for news,

I am very sorry to say "Vanity of vanities" there's no such thing as news— it is almost time for

the cholera, and then things will take a start!... Give our love to our friends, thank them

much for their kindness; we will come and see them and you tho' now it is not convenient.

All of the folks send love. Your aff Emily.

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886),

Letter to Austin Dickinson, 15 June, 1851

Dear Friend.

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886),

Letter to Thomas W. Higginson, June, 1877

Dear Friend,

— Emily Dickinson (1830-1886),

Letter to Charles H. Clark, mid-June, 1883

Dear Theo,

— Vincent Van Gogh,

Letter to Theo, London, 13 June 1873

Dear Theo,

— Vincent Van Gogh,

Letter to Theo, The Hague, 13 or 14 June 1883

My dear Theo,

— Vincent Van Gogh,

Letter to Theo, Arles, 13 June 1888

My dear Theo,

— Vincent Van Gogh,

Letter to Theo, Arles, 15 June 1888

My dear Theo,

— Vincent Van Gogh,

Letter to Theo,

Auvers-sur-Oise, 14 June 1890

My Dear Monsieur Faure,

— Edgar Degas (1834-1917),

Dear friend W. O'C

— Walt Whitman (1819-1892),

a hard day. Somber premonition of parting on the Königsplatz. Departure from Munich on June 30th.

Should this love not become my life and merely have been my most beautiful dream, then I shall find upon

awakening that strength has turned to bitterness. And woe to that which deceives, no matter how beautiful

it is. The powerful, the frightful truth shall win.

Do not ask what I am. I am nothing. I only know about my happiness. Do not ask whether I deserve it.

Know that it is rich and deep. I wanted to reach the goal before sunset. Near her. I had walked briskly.

But I had reckoned badly. The unspeakable longing for the goal made the many hours heavy. Over a wild pass,

I want to reach the gentle valley.

—

Paul Klee,

Diaries of Paul Klee, June 13, 1901

Tapering off; on the fourteen, departure at 12:35 p.m. From the Sezession exhibition, a few pictures

left a lasting impression: Zuloago [sic], The Bullfighter's Family,

Hodler:

Impressions of Four Ladies. The Glaspalast had nothing to offer.

—

Paul Klee,

Diaries of Paul Klee, June 14, 1903

I was so much in need of keeping my head perfectly cool, and now a downright tropical intermezzo fell

from heaven. I wandered about restlessly. Once I stood all of a sudden by the Aare. I had wandered

there so completely engrossed in myself, it was as if my brain had been burned out. What a sight—

suddenly the emerald, racing waters and the sunny, golden bank! I felt as if I had awakened from a

wild dream. For a long time I had not bothered to look at the landscape. Now it lay there in all its

splendor, deeply moving! How I had missed it, had had to miss it, because I wanted to miss it! Until

today I had led a life of thought, stern and void of the hot blood, and I shall go on leading it,

because I wish to do so. O sun, Thou my lord! The time has not yet come, the tangle of struggle

and defeat has not yet been unraveled. There are still swamps, warm vapors rise and collect between

me and the firmament, a host of arrows are turned against me.

Working with white corresponds to painting in nature. As I now leave the very specific and strictly

graphic realm of black energy. I am quite aware that I am entering a vast region where no proper

orientation is at first possible. This terra incognita is mysterious indeed. But the step forward

must be taken. Perhaps the hand of mother nature, now come much closer, will help me over many a

rough spot... I am ripe for the step forward.

—

Paul Klee,

Diaries of Paul Klee, June 1904

Granted: I am relatively satisfied with my etchings, but I cannot go on in this way, for I am not a specialist.

Nevertheless, for the time being, I won't drop it at all, but rather find the logical way out. A hope tempted

me the other day as I drew with the needle on a blackened pane of glass. A playful experiment on porcelain had

given me the idea. Thus: the instrument is no longer the black line, but the white one. The background is not

light, but night. Energy illuminates: just as it does in nature. This is probably a transition from the graphic

to the pictorial stage. But I won't paint, out of medesty and cautiousness! So now the motto is, "Let there be

light!" Thus I glide slowly over into the new world of tonalities.

—

Paul Klee,

Diaries of Paul Klee, June 1905

Toward evening, Head Physician Pickert came to see me and brought me the fifth number of the fourth year

of the Weisse Blätter, containing a small essay by Adolf Behne about my watercolors. Pickert

wanted all sorts of explanations about Expressionism and was exceptionally amiable. The paymaster gaped,

the "Doctor" and the young lady stared. How funny that my rising fame should have reached the Fifth Flying

School! And so I am no longer an obscure, workaday tool of a dauber, because it says so in the newspaper.

—

Paul Klee,

Diaries of Paul Klee, June 13, 1917

This is the first time in a while, Merline, that I recognize your writing from the good old days; even the envelope

was like one of your watercolors— and as for the letter, it seemed to have covered in one wing beat the entire

distance! Meline, Beloved, you know how I've wished that you might be able, independently of our sufferings and the

pains we have experienced, to feel as immanent and effectual the innumerable riches that from my heart have gone out

to yours. If you have managed to do so, how sweet will be the day of our reunion, my dear friend. If I never speak to

you of my heart it is because I have not yet dared to examine it since it slipped from the hand of that God

who shook it so strenuously during the months of work. I confess that I still feel as if I were convalescing from

those creative emotions, and a bit like one who, with trembling knees, comes down again from the highest peak, from

his elemental, unexplored, and ineffable nature...

You had no curiosity about my guests— and here again, coincidentally, I find myself once more in the midst of

a "series", but after the 15th or 20th of June there will remain only the K.'s ( a visit of the greatest importance)

to come, and, I hope, bring up the rear of this long processional of friendship. In any case, you'll find me at the

Bellevue for about another fortnight; I had long promised Frieda a few moments of vacation, for she had nothing left

to wear against the heat, which here (as everywhere) is beating down full force. I'm not sure of being able to bear

an entire summer in the Valais, without a little break from the heat somewhere. But I have no definite plans as yet.

And you, Dearest— please do not keep any more of your letters; send them all, especially those which might

tell me something of your ideas for the summer... Au revoir, Merline— write to René

— Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926),

Letter to Baladine Klossowska

I admit your accusation of impressionism and dogmatism. Suddenly, in a world full of tones and tints and shadows

I see a colour and it vibrates on my retina. I dip a brush in it and say, 'See, tha's the colour!' So it is,

so it isn't.

— D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930),

Letter to Helen Corke,

June 1909

My dear Lou,

— D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930),

Letter to Louie Burrows,

14 June 1911

My dear Mac,

Lord, it's a great thing to have met a woman like Frieda.

I could stand on my head for joy, to think I have found her. We've been together for three weeks. And I love her

more every morning, and every night. Where it'll end, I don't know. She's got a great, generous soul— and

a splendid woman to look at. But I'm afraid I sound a fool. You know I'm not frivolous. All this I say to you,

is really earnest. Do you know, I don't think you were fond enough of me. I was very fond of you. But you don't

trust yourself, or you don't trust other people. You won't let yourself be really fond, even of a man friend,

for fear he find out your weaknesses. As if your good qualities wouldn't outweigh, a dozen times, your failings!

But you mistrust folk— even decent folk. It is a blemish in you, a lack of courage, a want of faith and of

higher generosity. All this because you perplex and distress me so. Don't say it was only a mood, your last letter—

it was not. It is a permanent thing, this sadness of yours, because you feel your life, as a life, is going to waste.

Don't let it. Buck up and do something with it. Look at Aylwin too! Don't be angry with me, will you. Write and tell

me how you liked The Trespasser... It is Walpurgis Night festival tonight— I should have gone—

but it rains. Do you want me to buy you some Geographical picture-postcards, or anything down here? Tell me

if you do.

— D. H. Lawrence (1885-1930),

Letter to Arthur McLeod,

15 June 1912

My dear Mary

— D. H. Lawrence, Letter to Mary Cannan,

14 June, 1918

I may be blind. I looked for a long time at a head of reddish-brown hair and decided it was not yours.

I went home quite dejected. I would like to make an appointment but it might not suit you. I hope you

will be kind enough to make one with me— if you have not forgotten me!

— James Joyce (1879-1940),

Letter to Nora Barnacle,

Dear Miss Weaver: There has been so much hammering and moving going on here that I could scarely hear

my thoughts and then I have just dodged an eye attack. In fact when I was last writing to you I felt

pain and rushed off to the clinic where the nurse sent me on to Dr. Borsch. He said I had incipient

conjuncticitis from fatigue probably... I hope you have the Contact book. I put a few more puzzles

into my piece [Finnegans Wake, pp. 30-34]. I am working hard at Shem and then I will give Anna Livia

to the Calendar. Morel [French poet, Auguste Morel] will have to type all again as my typist is away.

I have got out my sackful of notes but can scarcely read them, the pencilolings are so faint. They were

written before the thunder stroke... Tuohy [Patrick Joseph Tuohy (1894-1930), Irish painter] wants to come

here to paint me...

— James Joyce (1879-1940),

Letter to Harriet Shaw Weaver,

Dear Lucia: Mamma has dispatched to you today some articles of clothing. As soon as the list of what you

want comes we will send off the things immediately... The heat clouds my spectacles and I see with difficulty

what I write! But you could hire a machine. At Geneva certainly you would find one. Something is always lacking

in my royal palace. Today is the turn of ink. I send you the programme of the Indian dancer Uday Shankar. If

he ever performs at Geneva don't miss going there. He leaves the best of the Russians far behind. I have never

seen anything like it. He moves on the stage floor like a semi-divine being. Altogether, believe me, there are

still some beautiful things in this poor old world.

Mamma is chattering on the telephone with the lady above who dances the one-step so well and fished my note

of a thousand lire out of the lift. The subject of the conversation between them is the lady on the fifth floor

who breeds dogs. These 'friends of man' hinder the lady on the fourth floor from meditating like the Buddha.

Now they have finished with dogs and are speaking of me.

I see great progress in your last letter but at the same time there is a sad note which we do not like.

Why do you always sit at the window? No doubt it makes a pretty picture but a girl walking in the fields

also makes a pretty picture. Write to us oftener. And let's forget money troubles and black thoughts.

Ti abbraccio...

— James Joyce (1879-1940),

Our last day— our last hour rather. I sit on a flat rock by the stream, while Hugh bathes.

We have just been talking about Woodstock, about the feeling we both have that we want to realize

the place, return home with a satisfying certainty that while we were here, we knew we were here and

we noticed everything, that our minds did not travel within a hazy shell of its own making. Usually

when people live in the city they are thinking of the country, and when in the country, of the city.

The New Yorker dreams of Paris while the Parisian wonders about New York. And we go through life

without definitely realizing any place. They all remain unreal to us. We speak of sensation that

our visit somewhere was like a dream. It happens sometimes, too, that the novelty of it is too sharp

for our slow-moving senses, and when we recover from the shock, it is already time to go. It demands

distance to see the thing as a whole.

— Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) Diary, June 15, 1924

We are reading and writing in bed. Today in spite of the rain I conquered my egoist's mood, which is so

hateful. I have been thinking of other things. Antonio [Valencia, 20-year South American old pianist],

for one, has been occupying my mind. He is with us

often now because he feels lonely and homesick. Il est la sagesse même [He is wisdom itself],

beautifully balanced, extremey intelligent and pure. He has very fine, soft eyes. His devotion to Joaquin

is remarkably unselfish and active and beneficial to my thoughtless brother. He has gentleness, very

modestly hidden learning, and no desire to shine at all. And he is talented. His quiet manner makes most

people overlook him— people like Horace, at least. But at concerts, he has won admiration and sympathy

before beginning to play, just by the way he comes on and by a charming simplicity. Last Christmas I gave

him a journal book like mine, which he is filling slowly. It is strange to see, with Horace, how necessary

talk is to keep pleasure alive. With Antonio it is not. He is one of the very few persons with whom you can

be absolutely silent.

— Anaïs Nin (1903-1977) Diary, June 14, 1926

There are supposed to be two 'I''s— the one is lower and unreal, of which all are aware [ego];

and the other, the higher and the real, which is to be realised [Self]. You are not aware of yourself

while asleep, you are aware in wakefulness; waking, you say that you were asleep; you did not know it

in the deep sleep state. So then, the idea of diversity has arisen along with the body-consciousness;

this body-consciousness arose at some particular moment; it has origin and end. What originates must be

something. What is that something? It is the 'I'-consciousness. Who am I? Whence am I/ On finding the

source, you realise the state of Absolute Consciousness.

The world is not external. The impressions cannot have an outer origin. Because the world can be cognised

only by consciousness. The world does not say that it exists. It is your impression. Even so this impression

is not consistent and not unbroken. In deep sleep the world is not cognised; and so it exists not for a

sleeping man. Therefore the world is the sequence of the ego. Find out the ego. The finding of its source

is the final goal... Can the world exist without someone to perceive it? Which is prior? The Being-consciousness

or the rising-consciousness? The Being-consciousness is always there, eternal and pure. The rising-consciousness

rises forth and disappears. It is transient... The world is the result of your mind. Know your mind. Then see

the world. You will realise that it is not different from the Self.

—

Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950),

Talks, June 15, 1935

Mr. Cohen desired an explanation of the term "blazing light" used by Paul Brunton in the last chapter of

A Search in Secret India.

Aurobindo advises complete surrender. Let us do that first and await results, and discuss further, if need be,

afterwards and not now. There is no use discussing transcendental experiences by those whose limitations are not

divested. Learn what surrender is. It is to merge in the source of the ego. The ego is surrendered to the Self.

Everything is dear to us because of love of the Self. The Self is that to which we surrender our ego and let the

Supreme Power, i.e., the Self, so what It pleases. The ego is already the Self's. We have no rights over the ego,

even as it is. However, supposing we had, we must surrender them.

Visitor: What about bringing down divine consciousness from above?

—

Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950),

Talks, June 14, 1936

When I entered the hall in the evening Bhagavan was saying: "Everything we see is changing,

always changing. There must be something unchanging as the basis and source of all this.

It is not mere thinking or imagining that the 'I' is unchanging. It is a fact of which

every one is aware. The 'I' exists in sleep when all the changing things do not exist.

It exists in dream and in waking. The 'I' remains changeless in all these states while

other things come and go."

— Ramana Maharshi (1879-1950),

Day By Day with Bhagavan

June. Luxembourg Gardens: A Sunday morning full of wind and sunlight. Over the large pool the wind

splatters the waters of the fountain; the tiny sailboats on the windswept water and the swallows

around the huge trees. Two youths discussing: "You who believe in human dignity."

Van Gogh struck by a thought of Renan: "Forget oneself; achieve great things, reach nobility and

go beyond the vulgarity in which the existence of most individuals stagnates."

— Albert Camus (1913-1960),

Notebooks 1942-1951, June, 1943 (pp. 74-76)

Beautiful day. A frothy light, shining and soft above and around the huge beeches. It seems

secreted by all the branches. the clusters of leaves stirring slowly in that blue gold like

a thousand mouths with multiple lips salivating all day long this airy, golden, sweet juice—

or else a thousand little contorted green bronze waterspouts ceaselessly irrigating the sky

with a blue and sparkling water— or else... But that's enough.

The end of the absurd, rebellious, etc., movement, the end of the contemporary world

consequently, is compassion in the original sense; in other words, ultimately love

and poetry. But that calls for an innocence I no longer have. All I can do is to

recognize the way leading to it and to be receptive to the time of the innocents.

To see it, at least, before dying.

— Albert Camus (1913-1960), Notebooks 1942-1951,

Dear Friend,

— Alexis Léger (1887-1975),

Letter to Dag Hammarskjöld,

Cher Alexis,

— Dag Hammarskjöld (1905-1961),

Letter to Alexis Léger, June 13, 1960

Now what is meditation? There are those who say that in meditation you must control your thought.

What does such control imply? It implies contradiction, which is a form of conflict. You try to

concentrate on something, and other thoughts creep in which you keep pushing away, so concentration

gradually becomes a process of exclusion. It is like the schoolboy who wants to look out of the

window, but the teacher tells him to look at his book, and the effort to look at his book is called

concentration. But such concentration is exclusion. I think there is a state of attention in which

concentration is not exclusion... In attention there is no conflict. Attention can be understood only

when you see the significance of trying to concentrate through control— which means that the

effort to concentrate ceases. As long as you are making an effort to concentrate, there is contradiction,

conflict; therefore, there is no attention, and you must have attention.

Meditation is not prayer. Prayer implies supplication, begging, and that is utterly immature.

You pray only when you are in difficulties. A happy man doesn't pray. It is only the sorrowful man

who prays, the man who is asking for something, or who is afraid of losing something...

What is generally called contemplation implies a center from which to contemplate; it means being in

a state to receive, to accept, and again that is not meditation. To lay the foundation for meditation,

one has to understand all this, so that there is no fear, no sorrow, no motive, no effort of any

kind. If you cease to make effort merely because someone has told you that you mustn't make effort,

you are trying to achieve that effortless state, and it cannot be achieved. You have to undertand

the whole structure of effort, and only then will you have laid the foundation for meditation.

That foundation is not fragmentary; it is not a thing to be gradually put together by thought,

by the desire for success, achievement, or in the hope of experiencing something much wider and

greater. All that has to stop. And when the foundation has been laid, then the brain becomes

completely quiet. It is no longer responding to any form of influence or suggestion; it has

ceased to have visions; it is no longer caught in or conditioned by the past. To be in that

state of quietness is absolutely essential. The brain is the result of centuries of time. It is

the biological, the animalistic result of influence, of culture, of the whole psychological

structure o society. And it is only when the brain is completely quiet, without a movement,

but alive, not made dead by discipline, by control, by suppression— it is only then that

the mind can begin to operate. But this absolute quietness of the brain is not a state to be

achieved. It comes about naturally, easily, when you have laid the foundation, when there is

no longer a division as the thinker and the thought.

All this is part of meditation; meditation is not just at the end of it. Laying the foundation

is being free of fear, sorrow, effort, envy, greed, ambition— free of the whole psychological

structure of society. When through self-knowledge the brain is no longer an accumulative machine,

then it is quiet, still, silent... But when there is that state of silence, then there is the coming

into being of that immensity, that unnameable. There is then neither acceptance nor denial; there is

no entity who experiences the immensity. There is no experiencer— and that is the most marvelous

part of it. There is only that immense, timeless movement, and if you have gone that far, you will

know what creation is.

— Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895-1986),

Fifth Talk in London, June 14, 1962

Dear Larry...

One of those almost imageless dreams visually, but nonetheless most vivid. In this dream I saw,

and was in communication with, a woman who was moving on a ground that moved under her. She had

no control over the ground, which seemed to carry her around at random and had no meaning, no visible

pattern or goal. But she was on the verge of a total choice, a conscious abandonment of her will to the

seemingly haphazard movement under her wherever it might take her. I then saw her after this choice, and

what before had been an unfocussed drifting here and there had become a controlled and beautiul pattern

in which every movement was highly conscious— though the actual motion of the ground remained

entirely the same. The "ground movements" were, of course, her fate, her destiny, and the thought

has long been familiar to me. The dream, however, was not just a repeated theme in the head; it was

an actual experience, an awareness of that which transcends both active and passive, meaningful and

meaningless, in a unity beyond words, although I still— rightly, I think— struggle to

express and define as precisely as is possible. Yesterday's talk with Barbara Mowat about The Tempest

was behind— or in front of— the dream.

— Helen Luke (1904-1995),

Such Stuff As Dreams Are Made On,

Russell Lockhart was here on Saturday. He and his wife have an old handprinting press and have produced

two books already. He gave me the second— a poem by Marc Hudson, "Journal for an Injured Son,"

very beautiful. It has brought powerful images to me, especially some words in the preface by Lockhart.

Marc wrote the poem for his brain-damaged baby— "These poems are not only a father's gift to his son;

they are a gift to the injured spirit in each of us."

The image came to me suddenly, the memory which has remained vividly alive in me all through the 75 years

since that day when I must have been about six years old. I am standing again in the small sitting room

of our flat in St. John's Wood and my mother is telling me— probably in response to my questioning—

about my father's death. I had known of course the fact that my father had died in India when I was eight

months old, and that was why I had no Daddy like other children. One day some children had come to visit

us with their parents, and I remember that I went up to the father and said shyly, "May I please sit on

your knees, because you see I don't have a Daddy," and he lifted me onto his lap. It is likely that this

growing awareness in me of loss led to that talk with my mother. I remember none of her words but her voice

broke as she told of how he had come to England on leave during those first months after my birth and had

spent much time carrying me round the garden of his parents' house where I was born. My mother had come back

to England before her confinement because of delicate health. We were about to go out to Bombay to join him

when the news came of his sudden illness and death. They had been intensely happy in their marriage; my

mother and others who knew him told me in later years of the extraordinary joy that he radiated to those

close to him, so that their angry moods or resentments somehow dissolved in his presence. When he died

while she was so far away, my mother told me, she too came near to death and cursed God, and only the

fact that I was there kept her alive...

When I read Marc Hudson's poems and Lockhart's words— "These poems are not only a father's gift

to his son; they are a gift to the injured spirit in each of us"— there came to me a yearning to

make "a daughter's gift to an injured mother." If only I could write of that experience in poetry,

I thought. Some single lines even formed in me. Anyone who has read Charles Williams's Descent into Hell

and has allowed the profundity of the images of "exchange" with an ancestor to enter into his or her soul,

will know that a "daughter's gift to an injure mother" through language, even many years after the mother's

death, may be valid. I do not think I could write an actual poem— I am no poet— but sometimes,

now and then, the spirit of poetry has entered into my prose writing, and that spirit springs out of the

images themselves.

One early morning this week I lay dozing, half dreaming, with a feeling of being in search of an image

for that experience of my childhood— and suddenly the image was there and I realized that all my life

I had somehow been waiting for it to become visible. It is very simple: I saw that at that moment, young as

I was, I had become a vessel— and my very body I saw as a dark, empty vase into which the grief

of my mother was poured and contained. Through the years, whenever the memory returned, I felt again the

almost unbearable pain of loss which entered into me, and was somehow aware of an extraordinary stillness

beyond tears; but never until now have I seen myself in that moment of time as a vessel, or know that I

would feel that she had poured into that vessel a gift from her inmost being, something that was mine

to carry, something that would give meaning to so much of my life.

Perhaps that experience was the beginning of the myth behind my life. It was the first real experience,

in the deep sense of the word, that I had known. For an "experience" is not a mere outer happening or

emotional reaction. It is something that an individual passes through consciously and learns from:

"ex" means "out of" and "per" is also the root of "peril" and implies the presence of danger. An experience

is born of a perilous happening which touches both conscious and unconscious and does not come to fruition

without work and imagination. Perhaps all true experiences must be carried in the vessel of our being,

sometimes for a lifetime, before they are born again in new creation.

— Helen Luke (1904-1995),

Such Stuff As Dreams Are Made On,

"My problems start when the smarter bears and the dumber visitors intersect."

— Ken Wilber,

One Taste: The Journals of Ken Wilber, Saturday, June 14, 1998

Random House asked for a literary title for Science and Religion (and could I use the words

"soul" or "spirit" or some such?). Oh well. Thinking of Oscar Wilde's great quote ["There is nothing

that will cure the senses but the soul, and nothing that will cure the soul but the senses"],

I suggested several variations on Sense and Soul, and they finally settled on

The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and Religion. So there it is.

So much for my diatribes against the commodification of the words "soul" and "spirit"—

I'm now guilty as charged.

— Ken Wilber,

One Taste: The Journals of Ken Wilber, Sunday, June 15, 1998

|

Born on June 14:

Charles-Augustin Coulomb

Harriet Beecher Stowe

John Bartlett

Alois Alzheimer

(1864-1915)

Karl Landsteiner

Margaret Bourke-White

Che Guevara (1928-1967)

Donald Trump

Eric Heiden

Steffi Graf

|

The American Revolutionary War began when the 13 colonies formed the Continental Congress and declared

their independence from the British. The first official flag, known as the Stars and Stripes or Old Glory,

was approved by the Continental Congress: "Resolved, That the Flag of the United States be 13 stripes,

alternate red and white; that the Union be 13 stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation."

According to legend, Betsy Ross (1752-1836), a seamstress from Philadelphia sewed the first American flag and

presented it to George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued a

presidential proclamation declaring June 14 Flag Day. It was not until August 3rd, 1949, that President Truman

signed an Act of Congress designating June 14 of each year as National Flag Day.

The American Revolutionary War began when the 13 colonies formed the Continental Congress and declared

their independence from the British. The first official flag, known as the Stars and Stripes or Old Glory,

was approved by the Continental Congress: "Resolved, That the Flag of the United States be 13 stripes,

alternate red and white; that the Union be 13 stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation."

According to legend, Betsy Ross (1752-1836), a seamstress from Philadelphia sewed the first American flag and

presented it to George Washington, George Ross, and Robert Morris. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson issued a

presidential proclamation declaring June 14 Flag Day. It was not until August 3rd, 1949, that President Truman

signed an Act of Congress designating June 14 of each year as National Flag Day.

The Bear Flag of the Republic of California was designed by William Todd,

nephew of Mary Todd (Mrs. Abraham) Lincoln. It was hoisted in Sonoma on June 14, 1846,

after a Mexican garrison was defeated by 33 revolutionaries.

Led by Captain Ezekiel Merritt and William B. Ide, they captures the Mexican General

Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo and his aides. The flag with a star, grizzly bear, and the words

"California Republic" flew for 26 days before being replaced by the Stars and Stripes on

July 9, 1846. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848 ended the Mexican War,

by the terms of which California is ceded to the United States. California was admitted

to the Union on September 9, 1850.

The Bear Flag of the Republic of California was designed by William Todd,

nephew of Mary Todd (Mrs. Abraham) Lincoln. It was hoisted in Sonoma on June 14, 1846,

after a Mexican garrison was defeated by 33 revolutionaries.

Led by Captain Ezekiel Merritt and William B. Ide, they captures the Mexican General

Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo and his aides. The flag with a star, grizzly bear, and the words

"California Republic" flew for 26 days before being replaced by the Stars and Stripes on

July 9, 1846. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848 ended the Mexican War,

by the terms of which California is ceded to the United States. California was admitted

to the Union on September 9, 1850.

.jpg) On May 10, German armed forces began their offensive against France, which had only 60 divisions,

and French General Weygand termed their deployment "a line of troops without depth or organization."

Artillery shelling and air cover helped the German army to breach the impermeable Maginot defense line.

The Wehrmacht routed the French army within a few days. The 37 French divisions were defeated or

surrendered en masse. The government fled from Paris to Bordeaux. German forces marched into Paris.

The next day, June 14, French military forces began to retreat from the Maginot Line. Columns of refugees

attempting to escape the conquering German army were savaged by Luftwaffe bombing raids on the roads.

On May 10, German armed forces began their offensive against France, which had only 60 divisions,

and French General Weygand termed their deployment "a line of troops without depth or organization."

Artillery shelling and air cover helped the German army to breach the impermeable Maginot defense line.

The Wehrmacht routed the French army within a few days. The 37 French divisions were defeated or

surrendered en masse. The government fled from Paris to Bordeaux. German forces marched into Paris.

The next day, June 14, French military forces began to retreat from the Maginot Line. Columns of refugees

attempting to escape the conquering German army were savaged by Luftwaffe bombing raids on the roads.

On June 14th the Argentine garrison in Port Stanley is defeated. The Argentine commander, Mario Menendez,

agreed to a cease-fire and surrendered as 9800 Argentine troops put down their weapons. On June 20th the

British formally declared an end to hostilities and established a Falkland Islands Protection Zone of

150 miles. This undeclared war lasted 74 days and claimed nearly 1000 casualties. The British took about

10,000 Argentine prisoners during the undeclared war. Argentina lost 655 men while Britain lost 236.

Argentina's defeat discredited the military government and led to the return of democracy in Argentina in 1983.

On June 14th the Argentine garrison in Port Stanley is defeated. The Argentine commander, Mario Menendez,

agreed to a cease-fire and surrendered as 9800 Argentine troops put down their weapons. On June 20th the

British formally declared an end to hostilities and established a Falkland Islands Protection Zone of

150 miles. This undeclared war lasted 74 days and claimed nearly 1000 casualties. The British took about

10,000 Argentine prisoners during the undeclared war. Argentina lost 655 men while Britain lost 236.

Argentina's defeat discredited the military government and led to the return of democracy in Argentina in 1983.

Alan Jay Lerner is best remembered for the many Broadway musicals he wrote with

long-time collaborator Frederick Loewe. These songs include Brigadoon (1947), Paint Your Wagon (1951),

My Fair Lady (1956), and Camelot (1960). They have become classics and were later successfully

adapted to the screen by Lerner who was also a noted playwright and a screenwriter. Born into a wealthy family

(the owners of Lerner's clothing stores), Lerner had a privileged education at Choate and Harvard.

He teamed up with Loewe in 1943 to write What's Up?, and the pair remained together through 1960

when Loewe retired. Lerner also worked with the Gershwins in An American in Paris (1951),

Burton Lane in On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1965), and Andre Previn in Coco (1969).

As a screenwriter, Lerner earned an Oscar for his screenplay and story for An American in Paris in 1951.

Seven years later, he won again for Gigi (1958). He and Loewe also shared an Academy Award for the film's

title song. In 1974, he and Loewe reunited to work on The Little Prince. Lerner and Loewe received

the prestigious Kennedy Center Award in 1985.

Alan Jay Lerner is best remembered for the many Broadway musicals he wrote with

long-time collaborator Frederick Loewe. These songs include Brigadoon (1947), Paint Your Wagon (1951),

My Fair Lady (1956), and Camelot (1960). They have become classics and were later successfully

adapted to the screen by Lerner who was also a noted playwright and a screenwriter. Born into a wealthy family

(the owners of Lerner's clothing stores), Lerner had a privileged education at Choate and Harvard.

He teamed up with Loewe in 1943 to write What's Up?, and the pair remained together through 1960

when Loewe retired. Lerner also worked with the Gershwins in An American in Paris (1951),

Burton Lane in On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1965), and Andre Previn in Coco (1969).

As a screenwriter, Lerner earned an Oscar for his screenplay and story for An American in Paris in 1951.

Seven years later, he won again for Gigi (1958). He and Loewe also shared an Academy Award for the film's

title song. In 1974, he and Loewe reunited to work on The Little Prince. Lerner and Loewe received

the prestigious Kennedy Center Award in 1985.

.jpg)

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina on August 24, 1899.

He was profoundly influenced by European culture, English literature,

and the philosopher Bishop Berkeley, who argued that there is no matter except mind.

Most of Borges's tales embrace universal themes— the often recurring circular labyrinth

can be seen as a metaphor of life or a riddle which theme is time. Although he was a

perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize, Borges never became a Nobel Laureate.

In 1961, Borges shared the International Publishers' Prize with Samuel Beckett.

He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa from both

Columbia and Oxford University. Borges was a small man, stooped, frail, white-haired

and blind for the last 30 years as a result of a hereditary disease. His soft smile

and sightless gaze masked the intricate mind of an author whose short stories are filled

with riddles and metaphysical humor. He was philosophical about his blindness, saying

"Blindness is no handicap for a writer of fantasy. It leaves the mind free and unhampered

to explore the depths and heights of human imagination." (Tulane University, Jan. 27, 1982).

Borges moved from Buenos Aires to Geneva early in 1986 after suffering from emphysema.

On April 26, 1986, Borges married his long-time secretary Maria Kodama, to whom he once

dedicated a book with the inscription, "You will be what I perhaps don't understand."

In his Preface to Borges' Labyrinths, André Maurois says Borges' stories

“suffice for us to call him great because of their wonderful intelligence, their wealth

of invention and their tight, almost mathematical style.” In "Funes the Memorious",

Borges tells about a man thrown off a horse and attained prodigious memory, recalling

daily cloud patterns, reconstructing all his dreams and waking hours. In "The Mirror

of Enigmas", Borges elucidates the work of the Jewish Cabalist Léon Bloy, saying

that every detail of our lives has symbolical value, concluding with what it is like

to have a

Jorge Luis Borges was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina on August 24, 1899.

He was profoundly influenced by European culture, English literature,

and the philosopher Bishop Berkeley, who argued that there is no matter except mind.

Most of Borges's tales embrace universal themes— the often recurring circular labyrinth

can be seen as a metaphor of life or a riddle which theme is time. Although he was a

perennial candidate for the Nobel Prize, Borges never became a Nobel Laureate.

In 1961, Borges shared the International Publishers' Prize with Samuel Beckett.

He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Letters, honoris causa from both

Columbia and Oxford University. Borges was a small man, stooped, frail, white-haired

and blind for the last 30 years as a result of a hereditary disease. His soft smile

and sightless gaze masked the intricate mind of an author whose short stories are filled

with riddles and metaphysical humor. He was philosophical about his blindness, saying

"Blindness is no handicap for a writer of fantasy. It leaves the mind free and unhampered

to explore the depths and heights of human imagination." (Tulane University, Jan. 27, 1982).

Borges moved from Buenos Aires to Geneva early in 1986 after suffering from emphysema.

On April 26, 1986, Borges married his long-time secretary Maria Kodama, to whom he once

dedicated a book with the inscription, "You will be what I perhaps don't understand."

In his Preface to Borges' Labyrinths, André Maurois says Borges' stories

“suffice for us to call him great because of their wonderful intelligence, their wealth

of invention and their tight, almost mathematical style.” In "Funes the Memorious",

Borges tells about a man thrown off a horse and attained prodigious memory, recalling

daily cloud patterns, reconstructing all his dreams and waking hours. In "The Mirror

of Enigmas", Borges elucidates the work of the Jewish Cabalist Léon Bloy, saying

that every detail of our lives has symbolical value, concluding with what it is like

to have a

.jpg)